|

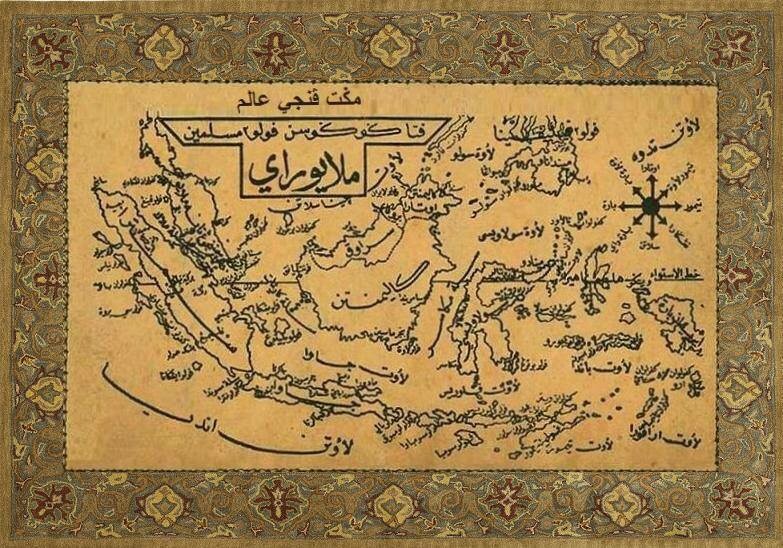

| The Malay World | Source: UTM |

Recently I had a conversation about affirmative action and quotas with a friend. Unfortunately because one of my blog posts about affirmative action and UiTM went viral a few years back, my circle of friends think I’m the go-to person for such conversations.

Pre-Ramble:

To give a bit of context to this conversation, there is a bit of twitter buzz going around about a man who was disappointed with quotas for bumiputeras in university and other higher learning institutions. I have my sympathies for the man, mainly because he had excellent results for SPM.

In response to his tweet, quite a number of people started claiming that his position has nothing to do with race. That whatever he faced was the luck of the draw. There were other Malay people who also brought up anecdotal stories on how they were declined placement in their preferred subjects or university.

In response to that response (yes, this is getting quite messy), many were arguing that the race based policies in this country are unfair. And they also argued that the Malays don’t deserve all these special preferences because they’re not really natives to Malaysia. In short, they were arguing the Malays are “pendatang” too.

Just to be clear, I understand the resentment of non-bumis who claim this. But the argument that “Malays are pendatang too” is problematic and could cause a lot more problems down the line.

Here are several reasons why:

The Other Pendatang: Colonizers

|

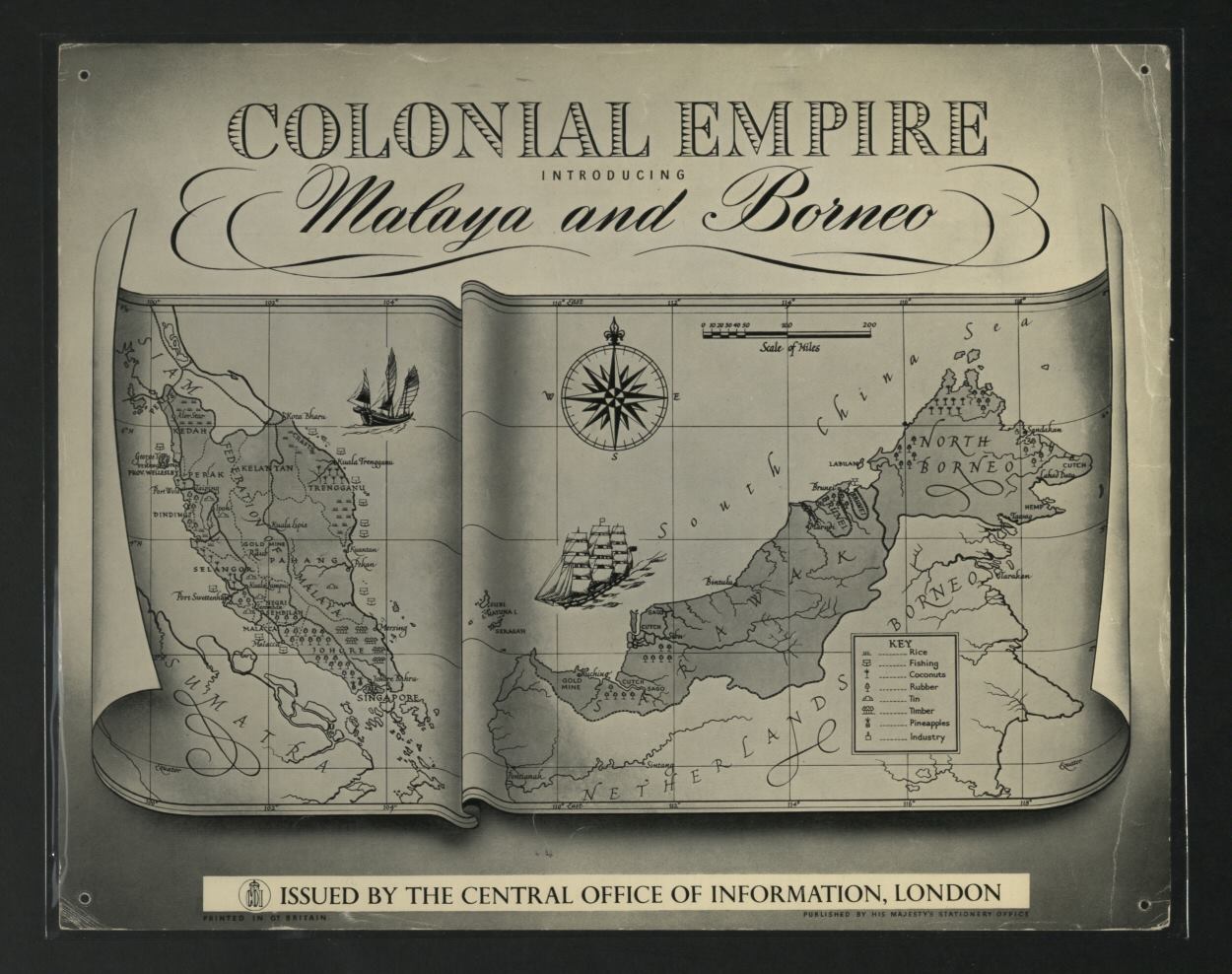

| British Map of What Became Malaysia | Source: UTM |

The borders of Malaysia are a social construct. Of course, just because I call it a construct does not mean the impact is any less real. Just like how race is a construct it does not mean the impact of race is any less real.

Prior to 1963, Malaysia didn’t exist and prior to 1957, Malaya wasn't a unified nation-state. These were inherited constructs from our colonizers. I would even further argue that while the idea of Malaysia had a utility for us, it was also the result of our colonizer’s intentions. Indonesia wasn’t an idea prior to the Dutch. The only reason why Indonesia exists today was because all the territories that’s under Indonesia today were Dutch colonies. Sure, there were polities that had some level of control over several islands, there was no political apparatus that glued them together as Indonesia.

Prior to all of this, the people of Sumatra, Java, and Sulawesi viewed Malaya and Borneo island as extensions of their world. They were not outsiders, but they were travelling from one patch of land to another, and they had no concept of borders as how British, Dutch, Portuguese colonizers did.

The ancestors of people who are considered Malays today, travelled back and forth these lands as part of the “Malay World”, another construct. But that construct held less of an importance in comparison to the inherited borders we have today. One example would be how Kedahan Malay is also spoken in pockets of communities in what are now Southern Myanmar, Sumatra in Indonesia, and parts of Southern Thailand. The same case when it comes to Kelantanese Malay being spoken in parts of Southern Thailand. As part of this unique history of the region, Malaysian and Thai citizens who were born in these neighboring states are allowed to travel back and forth without a passport. Presumably to reduce chances of possible border conflict, just like how not having a border between Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland reduced chances of conflict.

The opposite is also true, with the Cham people who travelled back and forth between what is now Vietnam, Myanmar, and parts of Hainan island also ended up on the shores of Pengkalan Chepa in Kelantan. The Javanese, the Bugis also travelled to our borders, thinking that they’re just an extension of their world.

So are the Malays pendatang then if I acknowledge that they had a diverse range of input from the surrounding regions? No, they did not see borders. They faced no opposition from any governing authority. The nationalist rhetoric surrounding borders of today is a modern creation.

If we continue to label who is a pendatang or not a pendatang will only empower them. It will only make them figure out a more puritan version of who exactly is a Malay person.

There are a thousand and one ways to combat discrimination in this country. But using the same rhetoric is obscuring history. It also allows people who actually had roots in the country to ask back why non-bumis are worried about who’s the pendatang or not when the lines are blurred, especially when it comes to visible minorities, the line isn’t as blurred. It also allows them to argue why aren’t the rest of you “assimilating”. While the lines are blurred for the recent input from the rest of the Malay archipelago, it’s easy for them to at least argue that there is some level of cultural similarity that doesn’t exist between them. Instead of destroying the concept of pendatang, it only creates tiers of who exactly is pendatang. It is such a gambit that further puts non-bumis as even more of an outsider.

I’m sure there are many of you then ready to rebut this asking what about the Orang Asli? Aren’t there stories of the Termiar people calling Malays pendatang? Aren’t Malay people encroaching the lands of Orang Asli too? Yeah, that’s true. But it does not mean the Malays did not see these lands as an extension of the Malay world and the Malay identity. It is sad that many Malays moved into the interior and displaced the Orang Asli, but both communities did live off the land or the surrounding lands. This is a conflict that needs to be resolved but at the same time both the Malays and the Orang Asli (who at the same time are very diverse), lived off the land and for generations saw the land as part of their world.

To double down on this pendatang rhetoric obscures that we are the result of European colonization. It empowers the idea that nation states are the one and only construct to determine who should get welfare or special privileges.

The Source of Power

|

| British Map of What Became Malaysia | Source: CBC.CA |

The other main issue with determining who should and should not get special preferences through their “native” status is that it obscures the source of power.

Let’s say that the Malaysian Malay world has learned to determine who’s bloodline was here longer. Let’s say they’ve created some kind of racial sciences that would make Adolf Hitler blush, will it empower Malaysian students who would like to get into university without any form of discrimination? You would still have native Malays exploiting their status. Even worse, you would still have non-natives still having power over the poor students who couldn’t catch a break.

Why is that the case?

It’s because true power lies in economic attainment. UMNO and their ilk understand it. If Malay privileges were to be gone tomorrow, the compounding power from their capitalist prowess will still be their insurance. Within the Malay world, income inequality is still huge. These are the same people who won’t need affirmative action in the long run but they could afford tutors, exposure to careers or live in a world where their family’s business is second nature. We’ll fall for the fact that they were meritocratic. But in reality their parents had seriously invested in their lives to get ahead.

The non-bumis will then have less of an ammo against them because the Malay elite will be able to say they’ve not benefited from government assistance.

The poor Malay in our world, have a very legitimate fear about being left behind. It is a bitter truth many non-bumis have to swallow. The urban rural divide is real. The Malay world is also very diverse. Culturally and economically. The socio-economic conditions of the Kelantanese Malay is very different from what Johoreans have to offer to the world. They’ve developed at different pace with different demands.

The culture of the intellectual elite of Malaysia unfortunately isn’t also Malay. I hate saying this, but there is a real reason why I’m writing this in English than Malay. The “intellectual class” aren’t very Malay. That is of course compounded by the fact that the Malay world does not have the economic prowess to shape it, and when they do the Western world is often seen as the outlet. Just look at how many on Malaysian Twitter associate the T20 Malay world with London. Middle class Malays either look at the land of our colonizers or if they take the spiritual path, the Middle East, the source of their religion and the second half of “proper” Malay identity. The perception of credibility isn’t internal but external.

Because of this insecurity, greater opposition to bumi privileges via challenging their native status would further push them into figuring out who to prove their “native-ness”. This will be a neverending exercise. The poor Malay will forever see the Malay elite as a beacon to create this new identity independent of the West. They want to be part of something that could pull them out of their economic woes. They see the Malay elite as the result of bumi privileges and think they could get there too. They technically could if they got in the right circles but it’s small. And on their path there, the very legitimate fear of being overtaken by rich or middle class non-bumi families is there. If they continue to see their bosses as non-bumi pendatangs forever, they will either demand the Malay elite to have greater control over the country’s businesses or see non-bumis as the source of their misery. The reality is that the rich non-bumis will forever cater to the Malay elite to gain favorable contracts or business leeway, over their own brethren. It’s patronage behind the gates, dog eat dog outside the gates.

So what’s the cure to this?

I know it’s easy for me to say this, but the easier way is to view things through the lens of class. The poor non-bumi should find a way to make poor Malay feel they have something in common with the discriminated non-bumi.

We cannot see bumiputera privileges just like how one sees white supremacy. The Malay world does not have a competing civilizational stake. They have a rich history of course, but it only empowers them in a small corner of the humanities. The poor Malay are after all a colonized people. They were once called the lazy native. A dangerous myth that even non-bumis piled on, making them fear the non-bumis further.

The better thing to do is to demand that non-bumis are treated fairer because of their economic positions. It is unfortunate that many non-bumis of this country are also hypercapitalistic thinking that they are in the tradition of the Robert Kuoks of this world. They view it as a way out and on their way out they step on the poor Malays thinking they’re leechers. This further empowers people like Mahathir by seeing that attitude as proof. And at the same time, feeds into affirmative action culture. The hypercapitalist T20 Malay elite are more than happy with this, securing their power sending their kids to the west as the rest of us beg for scraps.

If they were honest about using quotas as affirmative action, they’d invest more in the roots, the urban rural divide, making sure poor Malay kids also get the right standardized testing prep rather than hoping quotas will save the day.

Conclusion: Affirmative Action, Negative Approach

|

| Here's a Graduating Cat To Defuse the Political Tension | Source: Dreamstime.com |

Affirmative action is such a complicated topic in this country. I do think it’s useful. I am after all a benefactor of affirmative action. But at the same time opposition to it runs the risk of promoting hypercapitalist mentalities that don't improve the lives of anyone, pitting people in neverending competition. The idea that the Malays don’t deserve affirmative action because they’re pendatang obscures the complex realities of the Malay world, in favor of a simplified construct from our colonizers. It makes the Malay world more hostile, pushing the other “pendatang” out.

Also, has anyone pointed out that this conversation is so semenanjung centric? Am I a pendatang too then?

No comments:

Post a Comment